Visit these blogs to read about families who have adopted a child with this special need:

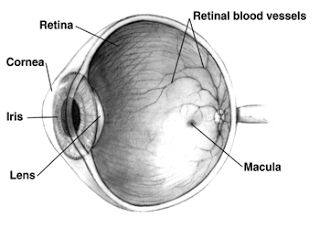

There are many types and levels of hearing loss. Problems with the outer and middle ear cause conductive hearing loss – the sound cannot be properly transmitted (conducted) to the inner ear and brain. Ear infections and fluid build up in the ears can cause temporary hearing loss, which can become permanent because of scarring (this can be common in children with cleft palate, as well as others). The outer ears may be malformed or missing (microtia) or the ear canals narrowed or closed (atresia). The middle ear structures may be malformed. Problems with the inner ear (usually the hair cells of the cochlea) or the auditory nerve cause sensori-neural hearing loss. It is also possible to have a mixed loss with both conductive and sensori-neural components.

“Normal” hearing is defined as thresholds between 0 – 20 across the frequency range. Mild hearing loss is thresholds between 20 – 40. Thresholds between 40 – 70 are considered moderate loss; severe loss are thresholds from 70 – 90, with profound loss defined as anything beyond that. Loss can be fairly “flat” across the frequencies, or “sloping” with more loss for some frequencies than others (a child might hear low frequency sounds at 30 dB but not respond to higher-pitched sounds until they are 80 dB – this would be described as a “mild-to-severe” loss). It’s important to note that purely conductive hearing loss falls in the moderate range. Files of children with microtia/atreia from China will often say they are “severely” or “profoundly” deaf, but this is usually not correct.

Medical Factors

Hearing loss can have a variety of causes: genetics, structural issues, maternal illness, childhood illness, etc. In many cases, the cause cannot be determined. Most children with hearing loss are healthy and have no other issues, but there are a number of syndromes within which hearing loss may be a component. Because the ears, eyes, heart, and kidneys develop (prenatally) at the same time, issues with one are sometimes associated with issues with the others. Children with hearing loss should have their eyes, heart, and kidneys checked upon coming home. Children with conductive loss related to fluid build up or damage to the ear drum may benefit from placement of tubes and/or tympanoplasty (reconstruction of the ear drum). Some children with microtia/atresia are candidates for surgical repair of the ear canal and/or middle ear, as well as cosmetic reconstruction of the outer ear. Not all families choose this route, however. Sensory-neural hearing loss generally cannot be “treated” or “corrected.”

Amplification

Many children with hearing loss benefit from amplification of various kids. Children with conductive loss (esp. microtia/atresia) usually use bone conduction hearing aids. These devices, which are worn on a headband by young children and can be attached to a surgically implanted post or magnet for an older child), transmit the sound through the bones of the skull directly to the inner ear. Most kids with purely conductive loss have near-normal hearing with these devices. For kids with mild or moderate sensory-neural loss, hearing aids that work by making the sound louder are often beneficial. Some children with severe or profound loss benefit from hearing aids, but often not enough to understand and develop speech. Kids with severe to profound loss may be eligible for cochlear implants (CIs), which are hearing prosthetics. The CI has internal components, which are placed during surgery, and external components which are worn like a hearing aid.

Communication and Education

Families of hard-of-hearing or deaf children have to make major decisions about language and communication, which also impact educational choices. These choices include whether or not to use amplification (hearing aids and CIs), what language to use (spoken English, American Sign Language, or some combination thereof), and what kind of school placement to select (regular classroom with speech and language therapy and other special education support as needed; deaf education program with self-contained classrooms in a regular school; a separate school for the deaf; or home education). The level of the child’s hearing loss, the child’s age at adoption, and the family’s philosophy and preferences all impact these decisions.

Families considering a Deaf or Hard of Hearing child should carefully consider these questions and research the options as well as resources in their local community. This is especially important when considering a child with a severe/profound hearing loss (most children with mild to moderate loss are able to use spoken language through the use of hearing aids and therapy). Becoming familiar with the cultural understanding of Deafness (the view that Deaf people are not a disability group as much a linguistic and social minority with their own language (ASL), history, community institutions, etc) is important. Families should understand that there is a developmental “critical period” for language learning and especially for auditory development and an older child (over preschool age) who has never had access to language may struggle to develop a variety of concepts and skills. These older children are fairly unlikely to become highly successful CI users, though they may gain some benefit from the device. Families adopting an older deaf child should assume that sign language will be the child’s primary communication method and should assess their own and their community’s resources to support this, particularly the opportunity to interact with other Deaf people and the availability of appropriate educational opportunities.

Resources:

American Society for Deaf Children

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association

Hands & Voices

National Association of the Deaf

Adopting a Child With Hearing Loss

ASL as a First Language

Ear Community

Cochlear

Gallaudet University

Signs for Hope

Read blog posts about Hearing Loss on No Hands But Ours.